Posted on September 29, 2023

Share:

The expansion of grain production and export represents a potential for Brazil’s economic growth, but the deficiencies in the logistics and storage

the-bottleneck-of-grain-storage-in-brazil-is-an-opportunity-to-expand-private-credit

The bottleneck of grain storage in Brazil is an opportunity to expand private credit

If, on the one hand, the expansion of grain production and export represents a potential for Brazil’s economic growth, on the other hand, the deficiencies in the logistics and storage sectors represent obstacles to the development of Brazilian agribusiness.

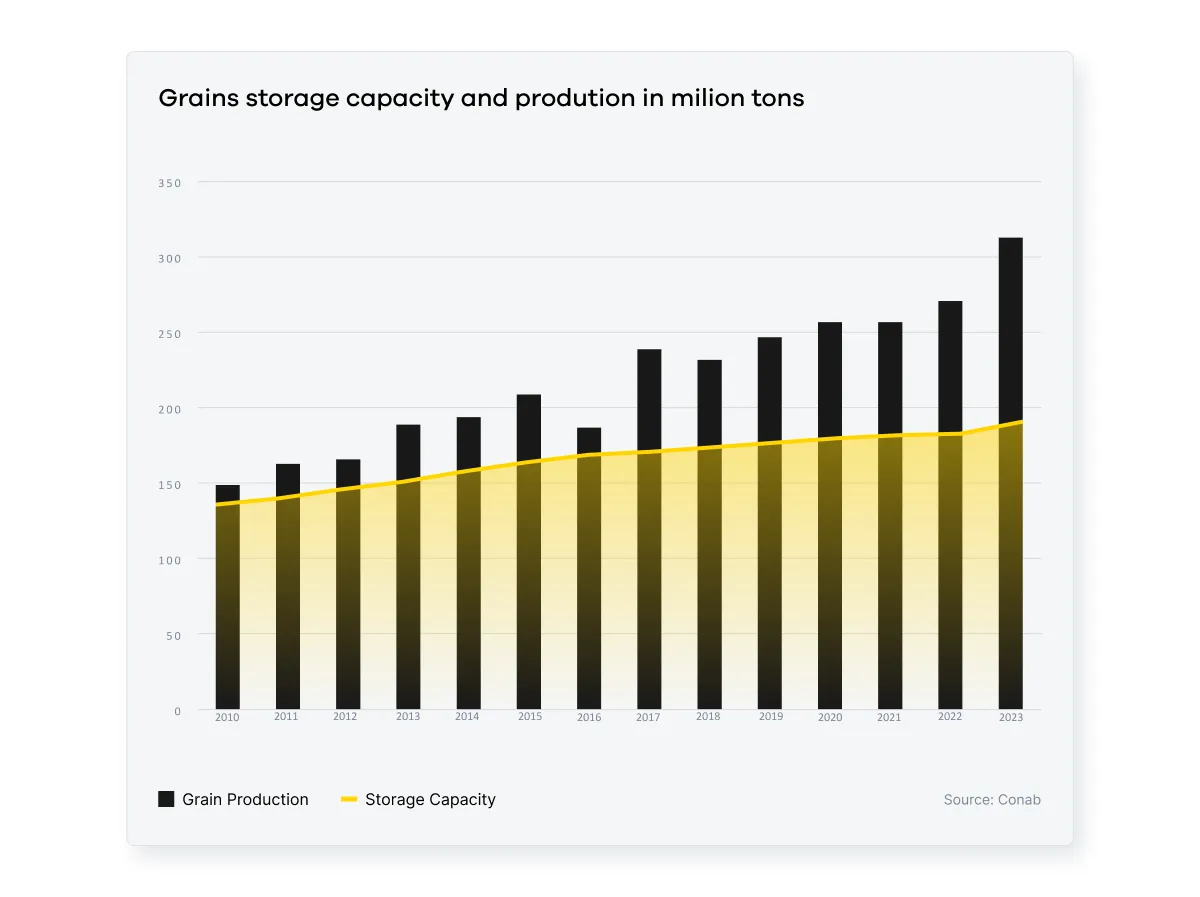

Grain Storage Capacity vs. Production

This is clear when comparing the growth in grain storage capacity with the increase in production from 2010 to 2023. The storage capacity was reduced by one-third since it reached 91% in 2010 and is estimated to be close to 61% in 2023. A percentage far from that recommended by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) suggests that a country’s storage capacity be 1.2 times its annual agricultural production.

Storage Infrastructure Challenges

Unlike the United States, where the storage units are close to or part of the farm complex, in Brazil, only 15% of the farms have warehouses or silos, according to Conab data. At the same time, the percentage is about 54% in the United States. In Canada, it’s about 80 percent. Besides, in Brazil, the grain storage infrastructure primarily consists of specific units for bulk storage (silos), which account for 78% of the total capacity. The other 22% are made up of conventional warehouses, which use bags and bales to store the product, presenting disadvantages in the conservation and loading and unloading operations of grains concerning the silo system.

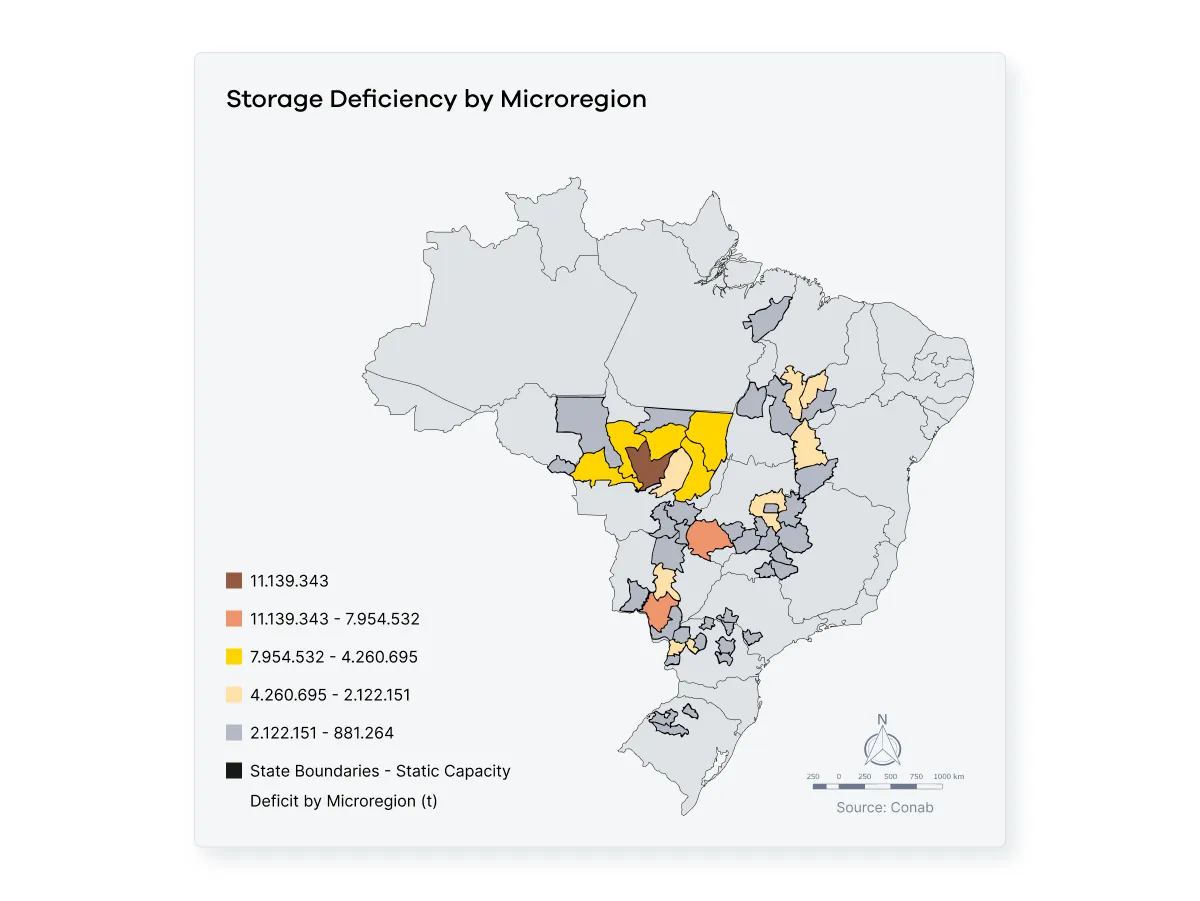

Regional Disparities

This feature became clear looking at the data that show that Brazil’s most significant grain storage deficit is concentrated in the Midwest, which is responsible for the most important national grain production. This occurs mainly in Mato Grosso, which, although it has the largest capacity to store grain among the Brazilian states, about 38 million tons, its capacity does not reach even half of its grain production.

This storage deficit exposes Brazilian grain producers not only in the Midwest region but throughout Brazil to significant economic losses since they need to sell much of their production during the harvest period, which implies assuming higher freight costs (these are significantly higher during the harvest period) and receiving prices below the international price for their product when using the value of the Chicago Stock Exchange as a reference.

With record harvests and the high grain storage deficit, soybean, and corn export premiums are at negative levels relative to the international market. According to the consultancy Cogo Intelligence in Agribusiness, only the losses generated to producers by the price difference can reach BRL 30.5 billion in 2023. Of the total losses, soybeans would account for BRL 19 billion, while corn would account for BRL 11.5 billion.

Photo by Pavel Voinov on Unsplash

Investment Needs

With the prospect of increased production, these losses tend to grow in the coming years if new investments in the storage sector are not made. A study conducted by Abimaq’s Grain Storage Equipment Sector Chamber (CSEAG) indicates that it would take about BRL 10 billion a year for ten years for the storage deficit to be zero by 2030.

However, the latest figures indicate that investments are far short of the storage capacity needed for production growth. The main (public) credit program for this purpose, the Warehouse Construction and Expansion Program (so-called PCA) of the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES), was made available in 2022 for only BRL 4.12 billion. The program provides credit of up to BRL 50 million to be paid in 12 years, with a grace period of up to 2 years, with interest rates between 7% and 8.5% per year, depending on the size of the storage unit. Recently, Banco do Brasil, and the New Development Bank (NDB) announced BRL 1.5 billion in credit to build warehouses.

Nevertheless, the historical average indicates that about 70% of the volume of public credit made available is granted. The reasons for the reduced demand are the excess of guarantees required, the high bureaucracy, low market interest in this type of project, and lack of perception about the “deficit” of storage and its costs.

Photo by Shot by Cerqueira on Unsplash

Potential Returns

According to Tadeu Vino, Commercial and Marketing Superintendent of Kepler Weber, Brazil’s largest company following post-harvest services, producers’ profits can be increased by about 15% with new storage facilities, allowing them to recover the amount invested in five or six years. When well maintained, with preventive maintenance, a storage unit can last more than 30 years. A study by the Thematic Chamber of Infrastructure and Logistics (CTLOG) indicates that an investment’s Internal Rate of Return (IRR) for this period would be 6% per year and that the average occupancy rate to make the business economically viable would be 62%.

Therefore, a storage investment deficit accumulates yearly of at least BRL 5 billion of credit while the sector earns losses of BRL 20 billion. Therefore, there is a potential for returns for producers and entrepreneurs who invest in this sector, in particular, in bulk storage (silos), just as there is a huge potential for the expansion of private credit for this purpose, with less bureaucratized sources of credit linked to the results of the ventures, allowing all parties involved to obtain part of the gains that the Brazilian commodity exporting sector will be able to provide in the coming decades.

Authored by:

Cristiano Oliveira, Associate Professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande — FURG andRivool collaborator.

Tiago Piassum, Founder of Rivool Finance.

Tags

Private credit